The Garden at Moorfield Journal: 55

The Marriage of Two Opposites. How the tension between two vastly different childhood memories of place, people and plants, play out in this garden. 15.04.2025

I was meant to share a piece on roses (that’ll come), funnily enough, it is the keystone plant to the childhood memory that is one half of the subject I am writing about today and all that is going on in my busy mind right now, or perhaps it has been for some time, maybe my whole life, in one context or another, been something I have wrestled to resolve. It is especially true, however, since becoming a gardener, and even more so since becoming the custodians of Little Oak, a former convict settled orchard on Melukerdee Country in South East Tasmania, 12 years ago and now here at Moorfield, a gold era former sheep station on Dja Dja Wurrung Country, in Central Victoria, this sense of being pulled between the two vastly different worlds I knew as a child which weighed on me equally in impact.

First, let me explain to those of you who may not have been reading me for all that long, or in amongst all of the plant and garden talk, missed the more profound pieces about the impact gardening has had on me. Together with the sometimes unconventional influences from my early years, I feel I have been somewhat lead to a career and life spent in nature, and will be eternally grateful for this as it subsequently has made me a much happier and at peace person, when it wasn’t always destined it would end up that way.

Little Oak was a place Hugo and I escaped to after we had had enough of living and working in the thick of Sydney city. I had been doing it for about 12 years, give or take brief sojourns overseas and to other states, when we moved. Hugo had been doing it most of his life, after the outer suburbs of a burgeoning Western Sydney full of families like his, newly immigrated from other countries, became home to Hugo, after coming from a politically ravaged Chile at the time, when he was just four years old.

Little Oak was a risk, it was a jump in the deep end and hope you swim, rather than sink kind of situation, whereby we came dangerously close to sinking more times than I can count. We were so busy surviving our great life-change/tree-change moment, and our having thrown caution, as well as stable jobs and income, to the wind, that most of the time, a lot of what we did there, was knee jerk, spontaneous and without that much investigation. We were just chucking everything at it, and figuring it out as we went.

And let me just say, there is nothing wrong with that either, we learnt so much by not knowing what we were doing and just getting stuck in, long before my formal education in horticulture began, and long before we really understood there were “rules” in gardening. Eventually, as I began to employ my design background into my garden work alongside my training, I noticed the mistakes I’d made and found my lane. I loved English style cottage and formal gardens, I thought, like the one that had made such a huge impact on me as a child growing up in an environment that couldn’t have been more foreign to this.

We were half way through our decade long life at Little Oak before I plunged us even further into financial chaos. I left the career I was now being paid a third of what Sydney based work did, for the same hours and levels of stress, and slowly losing my mind for its all consuming nature. I did this in order to spend my time around plants and gardens, and the people who dedicate their lives to them. I wanted to be one of those people, I was one of those people at my core, who can see now that the signs were there even as a little girl, growing up in Arnhem Land in a remote corner of Australia, and while visiting my maternal family’s multigenerational farm in the south of the north island of New Zealand. I would always be most “at home” in nature.

It is between these two seemingly antithetical worlds that I have been left loving two completely contrasting places, both having had a profound impact on me, my beliefs and values, my aesthetic, and with that, a tension that comes, and brings about a lot of too and fro in my thinking. I am a person who connects everything to everything and weaves a great web of stories, as you may now have realised, between these two points in my life especially. From here, all other decisions seem to be made and all sources of influence seem to first cross through these two very different frames of reference, before being distilled down into something that makes sense of how I see myself and why I make many of the decisions I do.

However, until now, my childhood spent in an environment you’d expect to see in commercials for the quintessential Australian experience of isolated expanses of land, great craggy cliffs of ochre coloured stone, sneaky crocodiles sinking below dark water, white sandy beaches and roos on red dirt, backlit by an equally red sunset, has played second fiddle to a more dominant core memory of my family’s very English farm, in terms of the landscape, and garden aesthetic, I thought I loved most. This is not because the former had a lesser impact, because it really didn’t but because there were rules around this kind of thing.

I loved roses, I loved big frothy cottage gardens around cute chocolate box cottages, big orchards, I loved farmhouses and homesteads, who generally always have the English style gardens that match the era they were built in. The world of exotic plants versus the world of native plants, are often at the epicentre of many a heated debate loaded with a plant lover’s puritanical reasoning, as to which we are best to build gardens with in this country, though one thing could almost always be agreed upon, they were viewed as separate to one another, they did not grow together or at least they did not grow together, well.

To look at Little Oak, the great explosion of blooms around a little white weatherboard farmhouse that in high summer almost entirely disappeared behind the floriferousness, you see the influences of my family’s farm, Oakview, of European abundance, the homage to the old country brought across the sea to the new, the first place I ever saw that idea played out. Where vast paddocks were grazed by livestock, and a beautiful old Victorian era home sat inside a world I found truly magical and spoke to the childhood literature I was read, of Peter Rabbit and that of Enid Blyton, English authors, English tales.

It was an English garden, an English way of life, in Aotearoa, aka New Zealand, with rose gardens, cut flowers, a vegetable garden and an orchard, a long lawn, perfectly clipped, and stands of oak on the gardens edge along the driveway and cypress for windbreaks along the farmland. It was, as a little girl, like seeing your family, who I didn’t grow up around most of the time, live inside the pages of your favourite books, stories you’d escape into, to get away from the cracks beginning to show in my home. It became fairytale like, in my mind, over time and where I was actually growing up, while entirely magical to me now, was attached to experiences at home which had begun to make me feel unsafe and life feel scary.

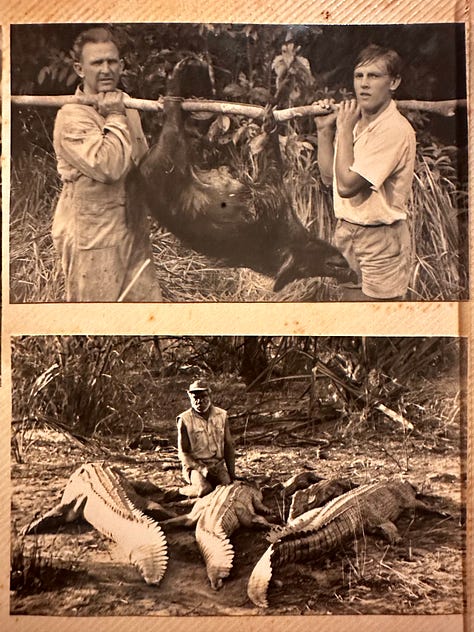

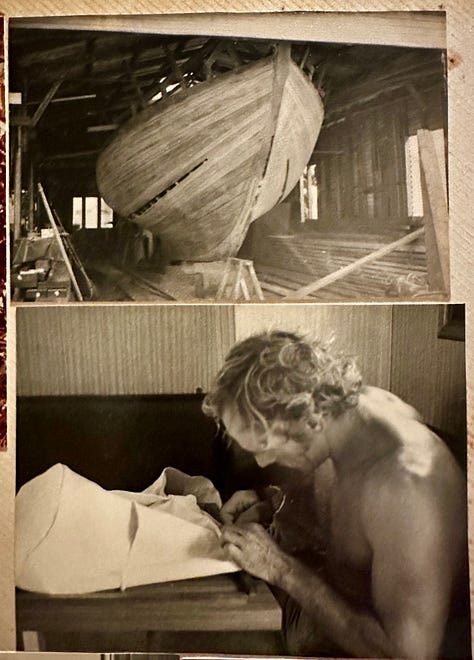

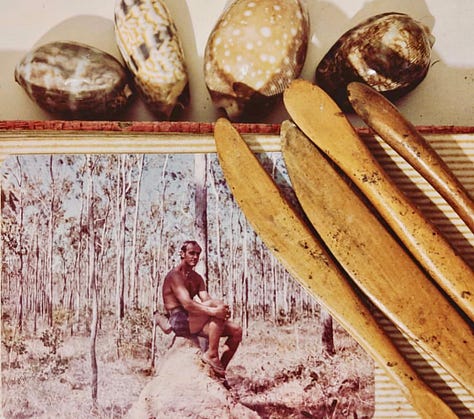

I was actually born there, in the Land of the Long White Cloud, which is what Aoteoroa means in Maori, to a Kiwi mother and an Australian father, before my parents returned home to Arnhem Land where they had met ten years earlier and lived, my father having been there even earlier, since the sixties. Some have said, that dad was the first yacht to sail into Arnhem Land on a boat he’d designed and built himself, called ‘Ataruka’, which meant moon in language, he once told me but I don’t remember from which indigenous nation, having spent most of his childhood with the indigenous people of North Queensland, a child runaway, helping to hunt wild pig in the mountain ranges we would later move back to, and “problem crocs”.

Later, after sailing around the South Pacific, he made his to a remote north eastern tip of the Northern Territory. It was the land of the Yolngu people, with whom dad was friends throughout my childhood, and who he was more comfortable in the company of compared to the people who moved in for the mine. A reclusive artist and a bushy since he was a boy, he liked being in nature most and therefore, because of this and because of his friendships, I spent a great deal of my childhood, living the same way he had growing up, barefoot on the beach and in the bush, hunting and eating in the dirt, climbing great granite boulders and ant hills, sitting around listening to language and laughter…….and having no concept of just how special this start to life was.

Arnhem Land was the antithesis of my family’s farm where the Queen hung on the wall in the polished hardwood hall, scones were made like one breathes and roses grew prolifically around a house rich in classic ornament. I was from a world of red dirt, bloodied by the iron oxide that it was rich in, and bauxite which brought the mine and alumina refinery and its crudely constructed homes they built for the community that worked it. Box like and without any fuss, I’d never known different but after visiting the farm, felt more like a shed to me. Lemon grass, ixora and mango trees grew in the simple gardens around them and no one was even attempting vegetable gardens. Food was flown and shipped into the community at great expense but then, mining made a lot of money.

It was both ridiculously hot and dry, or ludicrously humid and wet depending where in the year you were. A world of pandanus and stringy bark gum, of the most pristine white sand beaches and cerulean blue sea where outcrops of granite boulders, not unlike that which dot Moorfield and crown the hills around her and which attracted me to the area, were climbed by little intrepid me, on the edge of the sea. It was a world of grass trees and iridescent greens and dense black bark after it was routinely burnt as it had been for tens of thousands of years. Of buffalo and bauxite, black water lagoons and the sweet scent of lilac and white waterlilies and the snap of their fleshy stems. I was let to ride my BMX into the bush with the kids from the cul de sac we lived on and get lost for an entire day, and before and after school, in the natural world. We ate green ants, provoked the buffalo, searched for dingo and did our best to avoid crocs.

It is where my mind was permanently imprinted upon by a place where predators lurked where all water existed and I still struggle to swim in dark or deep water no matter where it might be. Where ancient ways were and still are practiced and I was privileged enough to be exposed to them. The idea of the spiritual, of that which existed that we couldn’t see but a knowing that it was present, none the less and all connected back into the natural world around us, was simply part of my belief system, and still is, so greatly influenced I was by all I was immersed into. It is the source from which that thinking, that way of being, that which you will often hear me explain how I experience a place, as believing the world of those passed on, is still ever present, first came to me.

It was where I would head out bush or to the beach with my dad in the old olive army landrover he owned, with family’s from Yirrkala to hunt with three pronged spears and thousands of years of skill and precision, and dad with a rifle slung over his shoulder, not so adept at hitting the target with the spear as those who had tried to teach him. Nests of croc eggs in marshlands, goanna, turtle and fish on the sand and in the red dirt, crackling fires, language and storytelling into the dropping sun and the sky of a trillion stars, and laughter, always so much laughter. It was, I know now, one of the truly most powerful and precious privileges of my lifetime, though for me as a little girl back then and for my late father, it was just a normal way to live.

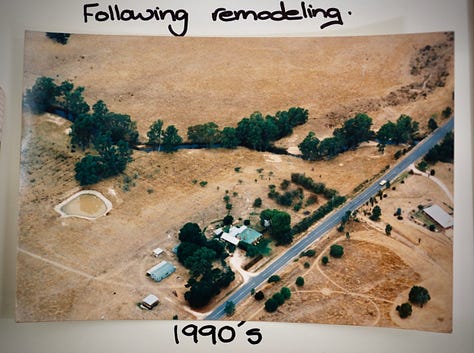

Now I sit in between the thick walls of a gold rush homestead on the land of the Dja Dja Wurrung, carved up to run thousands of sheep for over a century, Moorfield being the first European settlement home built in this community, built with the same bricks that built the church and the train tunnel. It was built on top of a rise in the land, overlooking a creek that has, according to records and stories, never run dry and was once a lot wider and from which lagoons bulged full with black perch. If you followed it north west, the creek, you would discover where it was carved out dry, mined for gold like all the other creeks and rivers here, that no longer run as a result, or barely, unlike the stretch that passes through Moorfield. Deep and everflowing, it was left alone by mining for it ran through prime farmland that fed the Gold Rush, siphoned off for the farms, changing its width and depth, flow and ecosystem.

If you walk the grasslands that roll down the slope of the land and run toward the creek, you will find swathes and swathes of Kangaroo Grass, an important food and cultural source for the Dja Dja Wurrung people. I became rather emotional when I realised I was standing amongst their knee high seed heads one high summer morning on a walk with Wednesday, our late pup, having just learnt about its significanse to the local indigenous people of this land, on an episode of Gardening Australia.

Now I look for it every year, make a mental note of where it grows and questions I need to ask those who know it best, about how to ensure it remains and if the great excavation hundreds and hundreds of Sulphur Crested Cockatoos, Corellas and Native Ducks have made of the ground where the Kangaroo grass grows, is in fact in search of its seed heads, to eat in a very dry summer. I am already anxious for next summer, to see how much returns.

We have built my mum’s cottage and a productive garden with a glassouse to counter the long cold periods between vicious summers, which consists of an orchard, a veg garden, a berry patch and picking garden of cut flowers, near these grasslands. There is a long border of tough crabapples, deciduous shrubs, lilac and perennials and a new hedge, after we removed 50 metres of an invasive African Boxthorn hedgerow that would be almost as old as the homestead, thorny as all get out and used to keep in sheep.

There is a rose garden, a herb garden and a dry garden around the pool we installed and then there is the bare land that runs between them all that we have drought tolerant gardens planned for. There are the tin sheds and a tin fence made from the old shearing shed by a previous owner, a 170 year old stone cellar that sinks below the ground by a couple of feet and offers respite at the hottest times of year and the foundations of multiple other outbuildings that have come down over the centuries.

It is, as it currently stands, very much a nod to the gardens of yesteryear in England, to my family’s farm, not just in its structure and formality with the glasshouse, the veg garden and orchard, the rose garden, the long border but it is also in how I garden. I don’t use chemicals, as my grandmother, great-grandmother and back we go, never did because there just wasn’t access to any, the concept was entirely foreign and I’m sure thought, entirely unnecessary. You ate seasonally and replenished the soil with organic matter from the farm to avoid disease, companion planted to manage pests, made homemade remedies and tended regularly to the garden, in order to keep them in check and reap the produce because it wasn’t just that there was no money to buy it instead, there was no shop from which to buy it in the first place. If a crop failed, you didn’t eat that thing, until next season.

My garden is kept mostly in check by systems I put in place from the beginning, systems like the aforementioned. I do the soil work and keep that up every year, I make sure I plant that which helps to attract and repel the helpful and unhelpful bugs, and I build in what is needed to create a healthy ecosystem that, after a while, starts to take care of itself, for the most part.

All of this aside, however, I am working on land that has no relationship and no history with any of the things I am growing and the practices I am undertaking other than in the last 200 years whereby the Fletcher family who built and ran Moorfield, immigrated from England in the early 1800s and Hannah and Emily Fletcher raised their families here and would’ve grown the same plants as I do now, and in the same ways. I love that I share this with them, they remind me of my own family, my own female farming forebears but I am made greatly uncomfortable by this, in the same breath, that this story alone denies this place, its oldest and first.

I feel like I am doing this garden an injustice by not better understanding or telling the whole story of this place, in the way that I can, through a garden. My daughter, however, who is deeply moved by the visits of the Dja Dja Wurrung to her Kinder and now school, knows far more about their stories for this place, than I do at just five years old. She sings songs she has been taught in a language spoken here for tens of thousands of years, asks me about endemic species that are culturally very important to the Dja Dja Wurrung people and why we don’t grow any of them? I answer, we will, I promise but how can I make these two seemingly very different garden types work together because there are “the rules”, or at least, I thought there were and there is my aesthetic for the gardens of my family’s farm.

Come forward and I am sitting in the theatre hall of the Melbourne Exhibition Centre, listening to James Hitchmough speak to Michael McCoy on the stage in front of me at the 2025 Australian Landscape Conference and as happened the last time I was at this event, a light bulb went off. Back in 2023 (the event is held every two years), I was listening to Fergus Garrett of Great Dixter in the UK, which I am now only a month away from going to learn with for a week in this most iconic garden, about organic practices and biodiversity in a formal garden setting and I felt like the guest speaker could’ve been speaking directly to me, once again.

Professor James Hitchmough, is an academic, teacher, practitioner, author and leader in the horticultural world and who, coming from the UK where he works in creating opportunities for biodiversity in urban spaces, is a passionate gardener and plantsman and mostly retired these days, spends a great deal of time building biodiversity into his own gardens. James is also one of the people working on Melbourne’s own Laak Boorndap, having spent a good decade working, teaching and researching in Victoria, Australia, at the University of Melbourne and holds a special affinity for native Australian plants and in particular, to species endemic to Victoria.

James Hitchmough knows these homegrown species as much as he knows his exotics, and after listening to James speak I became completely inspired. How he brushed off any rules and cast aside indoctrinated rhetoric around using only native species in an Australian garden setting, in favour of whatever combination of both native and exotic (as long as not invasive), has the greatest impact on biodiversty and demonstrates the best hardiness in our changing climate. Fast forward to the following day and partaking in the Naturalism through an Australian Native Lens Workshop, at Melbourne University and visiting Laak Boorndap, which means ‘Heaven’s Beauty’ in the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung language on whose lands the garden is being built, I am champing at the bit to begin creating my own native and exotic mixed naturalistic garden, here at Moorfield.

If you live in the Melbourne area, or are visiting, or are lucky enough to live in Victoria, you will one day be able to visit the entire new redevelopment of the Melbourne Arts Precinct, which will include a public urban garden space like nothing ever seen in an Australian city before and will, I believe, put it on the world stage alongside the likes of the High Line. This huge project is under construction now and still a number of years away but in the meantime, the Laak Boorndap Test Garden is ready to be explored. If you can, you should visit, the teaser garden of plant trials in real conditions for the greater project that James Hitchmough has helped spearhead alongside none other than, Nigel Dunnett himself, and Australia’s own flower maximalist, Jac Semmler of Super Bloom, the masterminds behind the Woody Meadow Project, Melbourne University Professor, John Raynor and Associate Professor Claire Farrell, and researcher Dean Schrieke, in collaboration with the team at Australian based Hassell headed up by Jon Hazelwood, and New York based, SO-IL.

I could barely contain my shock and awe at how seamlessly the marriage between exotic and native species had been made, seeing it firsthand in the company of its creators, bolstered by just how special that marriage between these two plant worlds can be, when done well. Gone was the jarring patchwork I so often see when these two general plant groups of native and exotic species are in the same room and the visual struggle to make them work together from a design aesthetic, not to mention their very different nutritional and growing condition needs and levels of hardiness against what are very hot summers and very cold, wet winters. Throw in the fact that the Test Garden is looking at how to maximise the vigour and floriferousness year round and in doing so, turn up the biodiversity opportunities of this urban garden, while minimising the water required to make it so, and it is speaking to me on so many levels of something I’d love to try and achieve here.

A quick video I put together of my visit to the Laak Boorndap Test Garden in Melbourne CBD which you can see uses a mix of natives and exotics together, and especially excited to see the use of Kangaroo Grass as an ornamental grass option - see the last two clips, amidst the look of a meadow-like, abundant cottage style native and exotic mix full of colour, form and movement.

So many questions I had were answered in a 24 hour period after years of trying to make sense of how I might make it work here, at Moorfield. How I go about acknowledging and honouring all the stories of this place, in a garden sense, in a way that still appeals to my design background and my need for balance and harmony in design. To find a visual way, a way through gardening to acknowledge the fact that I am on unceded land that was once the home of the Dja Dja Wurrung and all the life that flourished here before the colonial footprint that has been left behind in the form of the homestead and the boundary of Morrfield’s former sheep station history of almost 200 years, and that which broke a continuous line of culture that had existed for tens of thousands.

As many questions that have now been answered, many more come up in their place. More detailed questions about which Australian native species are endemic to this land that Moorfield is built on. What would have grown here before Moorfield was built and therefore, what will hopefully survive our devastating extreme frosts that come early and linger long into the warmer months that eventually turn blisteringly hot and bone dry? Conditions that have laid waste to most natives I have tested in the Dry Garden, thus far. Then what to grow alongside the successful homegrown candidates that won’t out compete them for space and nutrients, and will a perfect marriage make on the long slope that runs in front of mum’s cottage and borrows from the landscape beyond it, that includes the great granite monoliths, stands of majestic Red River Gums and ancient Kangaroo Grass Grasslands.

I have work to do, a lot, to truly understand what needs to happen here in terms of creating this garden and it is not a project I can, or should do in isolation to the source of this knowledge. To start a long quieted conversation with the people who called this land home, long before invasion and our settlement of it and to listen openly to the confronting truth of what would have happened here. To listen to the land itself and the people who understand it best and to my chilhood memories of places and people who could not have been more different but have come together in the making of me. To fully get my head around that which drives this need to create something that attempts, in a garden setting, to bring these two opposite worlds which both had such a profound impact on who I am as a person, a designer, a writer and a gardener, together, here at Moorfield, which itself has two very different stories to tell, and I hope, in part, to do so with the power of plants and place.

Thank you for being here, Pip xo

(See below for some other exciting news!)

A BOTANICAL ADVENTURE IS COMING…..AND SUBSTACK DIARY TO GO WITH IT!

As many of you now know, in just under a months time I am off on an adventure, a botanical adventure of epic proportions that I am still somewhat pinching myself over. First to spend a week learning from the great Fergus Garrett and the team behind Great Dixter at the garden itself in country England (still can’t quite believe that) and then to meet up with the family and explore a number of other iconic gardens throughout the UK.

This will also include a number of different gardens but also, a tour through King Charle’s organic garden which he has been creating for over 40 years, around his home, Highgrove , with a member of his horticultural team and the David Austin Gardens in the company of one of their Senior Rose Consultants, for all our rose lovers out there. I will also be attending RHS Chelsea Flower Show in London, a dream come true and am beyond excited to meet a horticultural hero of mine, Jo Thompson, in the flesh and to see her wonderful show garden, after chatting with her on this substack journey over the last couple of years. Jo being one of the first accounts and people to support and recommend my writing here on Substack for which I will forever be grateful.

We are then off to Paris and to Italy for family time but which will include a few more botanical explorations because I can’t help myself.

I will be keeping a diary of these experiences here on Substack for Paid Subscribers under our Garden Gadabout section of the Garden at Moorfield, which will include photo galleries, short videos and written entries of the experience of visiting these incredible gardens and share with you what I learn about what has gone into creating them. This month I will put together a schedule of what these publications will be, which gardens I am seeing and when, and what you can expect as a paid subscriber to receive over the course of the month and beyond as I digest all I will experience on this once in a lifetime opportunity.

If there are gardens in Paris or Italy that you think I simply must see, let me know, I am always excited to learn from those who know, what else is out there. So, on that note, stay tuned for the itinerary of gardens and if you are a Free Subscriber currently but wish to go on this journey with us, it is $50 for the year, or $5 each month, a price I’ve not put up in the couple of years I have been here on Substack writing about my gardening adventures, both at home here at Moorfield, and beyond, be it within Australia or abroad. Upgrade to paid below….

Beautiful and very informative, thank you

Beautiful piece, Pip, I'm so looking forward to what you'll create ❤️